Probiotics have become enormously popular, expected to reach $42 billion dollars in global sales this year. [1] This is due largely to our rapidly expanding knowledge of our microbiome and the impacts of gut bacteria on aspects of our health ranging from body composition, mood, genetic expression, immune response, and beyond. There is even a growing field of neurogastroenterology studying the bidirectional communication of the brain-gut axis.

Many of the benefits people report from probiotic use have evidence showing they may indeed be beneficial including relief from antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children [2] and other causes of diarrhea such as C. difficile infection, [3] improved bowel movement and consistency, reduced inflammation associated with the intestinal tract, decreased symptoms of allergy and eczema, and aiding immune function to name a few. [4] Sometimes, however, probiotic supplementation fails to meet expectations. Why is that?

1 – Overgrowth

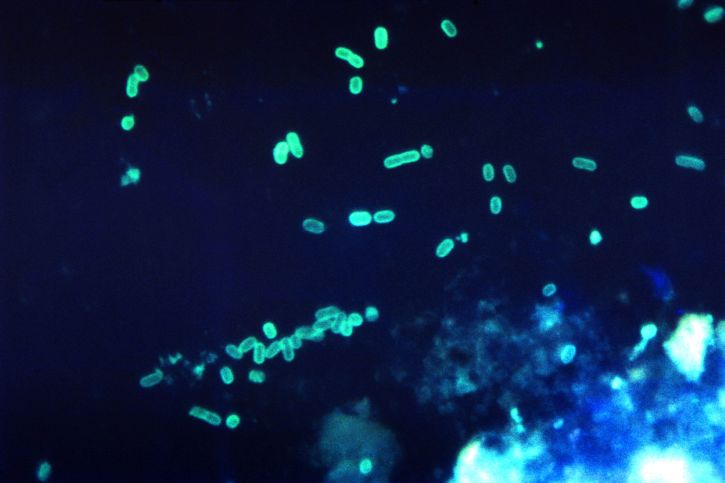

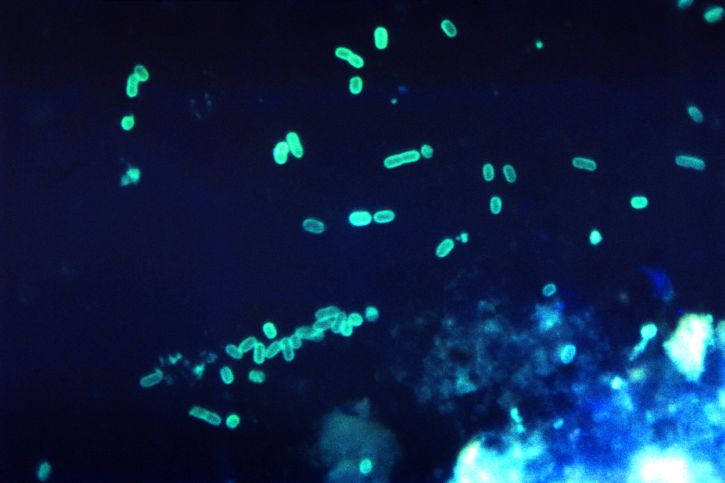

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of E. coli (Credit: NIAID)

This translates to too much competition and not enough living space for the newcomers. Sometimes overgrowth takes the form of SIBO (Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth) but overgrowth could also be dysbiosis, or an overgrowth of certain bacteria in the large intestine where most of the bacteria are supposed to be. When you add a tiny amount of bacteria (5 billion-100 billion in a sea of 100 trillion or more) it may be hard for the introduced bacteria to move in.

2 – Your diet is not providing the right environment

Certain diets are more conducive to the growth of good bacteria, like those high in resistant starches (non-digested vegetable fibers that benefit your intestinal cells and bacteria). These microbiota-accessible carbohydrates are crucial in shaping the microbial ecosystem but tend to be very low in the standard Western diet. [5]

Other foods not only do not support good bacteria but can actually have adverse effects on your microbiota. Diets very high in animal protein appear to alter the gut bacteria and increase levels of atherosclerosis markers (associated with plaque formation in the arteries). [6] High-fat diets have been linked to negative impacts on the gut microbiome and these changes have been theorized to play a role in the development of chronic metabolic diseases. [7]

More studies need to be done in this area to further clarify the types of fats and proteins that would cause these changes. Most studies that find these correlations are looking at the high fat, high protein standard American diet without differentiating a diet high in healthy fats like those found in nuts, avocado, and olive oil or less inflammatory animal proteins like wild-caught fish and grass-fed beef.

Mice that had reduced microbial diversity secondary to a low fiber diet had more difficulty reversing these changes when several generations of mice had consumed a Western-style diet. This low diversity was in fact not reversible with improvement in diet alone. It was also not effective to introduce the missing microbial taxa without the supportive dietary component. In one study performed on mice, both the missing microbes and the right environment need to be administered together for successful return to the original diversity. [5]

3 – You aren’t using a probiotic fertilizer

Chicory, a common source of inulin (credit: geography.org.uk)

Ideally you have the perfect diet to provide the perfect environment for good bacteria. For some this would constitute a major dietary change, which is not only difficult for most people, but even if your diet is good, getting the probiotic that you want to stick can still be a challenge. Sometimes using a probiotic “fertilizer” can help these changes happen faster. What is a probiotic fertilizer? These contain substances that help support the growth beneficial bacteria while impeding the growth of pathogenic organisms as well as creating supporting architecture, and improving the health and environment of intestinal cells. Ingredients might include arabinogalactans, oligosaccharides, plantain, inulin, and astaxanthin for example. [8] [9]

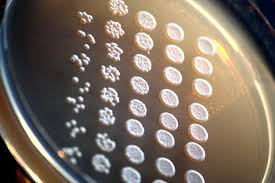

4 – Your probiotic contains no live organisms

This is a major concern with supplement quality, but sometimes the blame is not with the company who made it, but sometimes with the distributor, retailer, or consumer who may not have stored the probiotic correctly. Most probiotics need to be refrigerated or in the very least not exposed to heat, so the assurance that it was stored properly is a reason enough to buy directly from the company who makes it, or from a provider who orders from them, otherwise you may be wasting your money. Additionally, the probiotic label should contain labeling declaring how many organisms are present at the date of expiration. Such claims should be backed up by 3rd party assays, not just a certificate of analysis from the supplement company’s supplier. If you have concerns about whether your probiotic comes from a reputable source, ask your doctor.

5 – You’re using the wrong species

We are far from knowing all there is to know about which species of bacteria do what in different people and with various conditions, and because probiotics are considered to be a food supplement in the US they are not required to show they are effective, though they cannot make health claims without the FDA’s consent.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae (credit: Rainis Venta)

We do however have some research to support the use of certain species in some circumstances. For example, Saccharomyces boulardii, a type of yeast, has evidence of benefit as a conjunctive treatment in Crohn’s disease through anti-inflammatory action mediated by immune cells [10] [11] and can help restore intestinal cell integrity after injury often seen in conditions like irritable bowel disease. [12] In a systematic review and meta-analysis S. boulardii was also shown to be safe and effective for several types of diarrhea and shows promise for treatment or prevention of a number of conditions including Crohn’s disease, IBS, C. difficile infection, HIV-related diarrhea, and giardiasis. [13]

Other species have less evidence but still show promise. Bifidobacterium breve for example was shown to decrease production of an inflammatory marker (TNF-α) in children with celiac disease, [14] but larger scale meta-analyses have not yet been performed.

For constipation, a review of 5 RCTs resulted in improved stool consistency and frequency with Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010, Lactobacillus casei Shirota, and Escherichia coli Nissle 1917. [15]

Probiotic formulas are also becoming much more specialized as research supports specific uses, such as for immune function. A 2012 study in the British Journal of Nutrition showed that Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis, BB-12® and Lactobacillus casei 431® may help augment immune response, though specific applications of this use have not been studied extensively. [16] Along these lines of immune support, other strains have promising research such as that for Lactobacillus plantarum HEAL9 and Lactobacillus paracasei 8700:2 which were shown to alleviate symptoms of common cold and cold duration when taken daily over 12 weeks. [17]

The general consensus with probiotics is that more research is needed to help further understand the medical applications of specific species and strains.

The right strain for you may not be the right strain for other people with the same symptoms

Lactobacilli (credit: Ricardio Ariotti)

Additionally, the balance of bacteria in your gut is different from other people. There are tests that can help determine what bacteria are present through a stool test that may be able to help guide your probiotic decisions. If you have high levels of Lactobacillus acidophilus, using this bacteria species as a probiotic is likely not going to make much of a difference.

6 – The strain of bacteria you have is different than those in the supportive research

If you think back to biology class, you’ll remember the genus and species of an organism. For example the scientific name for humans is Homo sapiens where Homo is the genus, and sapiens is the species.

When it comes to probiotics, there’s another important identification of the organism: the strain. The strain is a genetic variant or subtype. On a probiotic label this will be displayed as a short series of numbers and letters (such as BB-12 or 431 with examples mentioned above). Actions of bacteria can vary between individual strains of the same genus and species of bacteria. For this reason, studies that support the use of specific bacterial species for the treatment of specific conditions should ideally only be applied to the strain studied. In one study only 2 of 44 probiotic supplements were identified at the strain level. [18]

7 – The probiotic you’re using has a misidentified organism

Unfortunately, studies have found improperly identified organisms in probiotics, different species, or different amounts than stated on the labels. [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] So even if you’re using an evidence-supported probiotic for a condition, you might not be taking the bacteria you think you are. Quality and standards by the company that makes the probiotic are therefore very important.

8 – You aren’t addressing the cause of your symptoms

E. coli (credit: Charles Farmer)

Having a bacterial imbalance or low diversity of bacterial strains is quite common with our high use of antibiotics, non-optimal diets, and lower exposure to bacteria than humans once had. [23] However, low Lactobacillus, for example, may not be the issue or if it is an issue it still might not be the cause of your symptoms.

It is important to get a diagnosis so you know you aren’t overlooking some serious problems. While many cases of bloating can be attributed to bacterial imbalance, symptoms like bloating and feeling full quickly can be a sign of something much more serious, like ovarian cancer. Abdominal pain or discomfort can have numerous causes like fatty liver disease, food intolerance or allergy, gallstones, pancreatitis, endometriosis, diverticulitis, and ovarian cysts to name a few. With the right diagnosis you will be able to address your symptoms more effectively.

Probiotics are generally safe with very few adverse events however, they are not for everyone. This is particularly true for people with a weakened immune system where serious complications including infection are possible. Serious adverse events have been reported in certain populations such as immuno-compromised children with central venous catheters or disorders of fungal or bacterial translocation, however no adverse reactions have been reported in otherwise healthy children. [2] More common side effects that are not considered severe can happen in generally healthy people such as mild abdominal distention and discomfort.

For those of you who read the systematic review in Genome Medicine that concluded there is a lack of evidence for an impact of probiotics on fecal microbiota composition in healthy adults, or perhaps The Guardian’s rash judgement that probiotics are “a waste of money,” I hope that you now have a better understanding of why there are problems with these statements. Furthermore, the studies in the systematic review were unfortunately not all of particularly good quality, making the review fall short as well. After all, a systematic review is only as good as the studies it contains.

The studies they used were also designed too differently from each other for a meta-analysis to be performed. They excluded studies where there was concurrent supplement use (so certainly no prebiotic supplements were used), they used organisms from 3 different genera (Bifidobacterium, Bacillus, and Lactobacillus) that were not strain identified and they used varying methods of conveying the probiotic to the patient’s gut (e.g. biscuit, milk product, pill). Only 2 studies that were included looked at the diet of the individuals in the study. We know diet can have a profound impact on the bacteria that thrive and the right foods can offer prebiotic properties and the wrong diet can certainly hinder the good bacteria from moving in. Other limits of the study included that the probiotics were only used for a couple of months, the age range was rather broad, with some studies focusing on particular age groups, and subjective benefit was also not addressed. I could go on, but instead I’ll leave it to the NIH that wrote this piece addressing some of these concerns and more.

Disclaimer: These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is for educational purposes only and are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease. Please consult your healthcare provider for guidance about a specific medical condition.

Works Cited

- Albenberg, L. G., & Wu, G. D. (2014). Diet and the intestinal microbiome: associations, functions, and implications for health and disease. Gastroenterology, 146(6), 1564-1572.

- Berkeley Wellness. (2014, March 3). Probiotics Pros & Cons. (University of California Berkeley) Retrieved June 2016, from http://www.berkeleywellness.com/supplements/other-supplements/article/probiotics-pros-and-cons

- Bodera, P. (2008). Influence of prebiotics on the human immune system (GALT). Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov, 2(2), 149-53.

- Busch, R., Gruenwald, J., & Steffi, D. (2013). Randomized, Double Blind and Placebo Controlled Study. Food and Nutrition Sciences, 4, 13-20.

- Canganella, F., Paganini, S., & Ovidi, M. (1997). A microbiological investigation on probiotic pharmaceutical products used for human health. Microbiol Res, 152, 171-179.

- Canonici, A., Pellegrino, E., Siret, C., Terciolo, C., Czerucka, D., Bastonero, S., . . . André, F. (2012). Saccharomyces boulardii improves intestinal epithelial cell restitution by inhibiting αvβ5 integrin activation state. PLoS One, 7(9), e45047.

- Chmielewska, A., & Szajewska, H. (2010). Systematic review of randomised controlled trials: Probiotics for functional constipation. World J Gastroenterol, 16(1), 69-75.

- de Vrese, M., & Schrezenmeir, J. (2008). Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol, 111, 1-66.

- Gilliland, S., & Speck, M. (1977). Enumeration and identity of lactobacilli in dairy products. J Food Prot, 40, 760-762.

- Goldenberg, J., Lytvyn, L., Steurich, J., Parkin, P., Mahant, S., & Johnston, B. (2015). Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(12).

- Goldenberg, J., Ma, S., Saxton, J., Martzen, M., Vandvik, P., Thorlund, K., . . . Johnston, B. (2013). Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(5).

- GR, G. (1999). Dietary modulation of the human gut microflora using the prebiotics oligofructose and inulin. J Nutr , 129(7), 1438S-41S.

- Hamilton-Miller, J., & Shah, S. (2002). Deficiencies in microbiological quality and labelling of probiotic supplements. Int J Food Microbiol, 72, 175-176.

- Hughes, V., & Hillier, S. (1990). Microbiologic characteristics of Lactobacillus products used for colonization of the vagina. Obstet Gynecol, 75, 244-248.

- Klemenak, M., Dolinšek, J., Langerholc, T., Di Gioia, D., & Mičetić-Turk, D. (2015). Administration of Bifidobacterium breve decreases the production of TNF-α in children with celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci, 60(11), 3386-92.

- McFarland, L. (2010). Systematic review and meta-analysis of Saccharomyces boulardii in adult patients. World J Gastroenterol, 16(18), 2202-22.

- McKay, D., & Blumberg, J. (2007). Cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon) and cardioavscular disease risk factors. Nutr Rev, 65(11), 490-502.

- Murphy, E., Velazquez, K., & Herbert, K. (2015). Influence of high-fat diet on gut microbiota: a driving force for metabolic disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 18(5), 515-520.

- Orel, R., & Kamhi, T. T. (2014). Intestinal microbiota, probiotics and prebiotics in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol , 20(33), 11505-24.

- Rizzardini, G., Eskesen, D., Calder, P., Capetti, A., Jespersen, L., & Clerici, M. (2012). Evaluation of the immune benefits of two probiotic strains Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis, BB-12® and Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei, L. casei 431® in an influenza vaccination model: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Nutr, 107(6), 876-84.

- Segata, N. (2015). Gut microbiome: westernization and the disappearance of intestinal diversity. Curr Biol, 25(14), R611-3.

- Sonnenburg, E., Smits, S., Tikhonov, M., Higginbottom, S., Wingreen, N., & Sonnenburg, J. (2016). Diet-induced extinctions in the gut microbiota compound over generations. Nature, 529(7585), 212-5.

- Thomas, S., Metzke, D., Schmitz, J., Dörffel, Y., & Baumgart, D. (2011). Anti-inflammatory effects of Saccharomyces boulardii mediated by myeloid dendritic cells from patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 301(6), G1083-92.

- Weese, S. J. (2003). Evaluation of deficiencies in labeling of commercial probiotics. Can Vet J, 44(12), 982-983.

Thanks for putting that together.