This article was originally published at Whole Health Associates’ website

By Aylah Clark, ND

The exercise supplement industry is thriving as the popularity of weight lifting in particular has increased. I love that weight-lifting is becoming more popular, especially among women, but there is a lot of misinformation out there. This doesn’t mean you should avoid exercise supplements completely however because some do have a lot of evidence behind them.

Although getting nutrients from food is ideal, sometimes supplementation around exercise can actually be very helpful in optimizing the right nutrients at the right time. If you are supplementing are they working for you? Are you taking the right ones? Are you taking enough or even at the right time?

Foundationally, the right diet with appropriate proportions of macronutrients (protein, fats, carbs) in the form of healthful foods, adequate sleep and recovery, and good exercise techniques are essential. As we get those ducks in a row, we can also move toward optimizing specific nutrients and their timing which I focus on here.

Not all of the supplements mentioned are right for everyone or every workout routine but for some they can give your body just what it needs to see the results you’re looking for, whether that is muscle-building, enhancing endurance, weight loss, or some combination. This isn’t to say there aren’t other supplements that work as well. To reiterate, none of these options can take the place of the right exercise program, a healthy diet, and adequate sleep.

(Full disclosure: We do offer these nutritional supplements in our office but I’m not advocating one supplement brand or another as long as the quality is high.)

Branched-Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs)

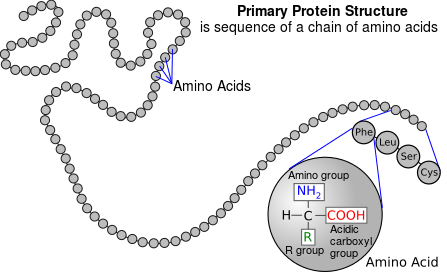

Of supplements studied for applications in exercise, BCAAs show some of the most promise. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. There are 3 that have branched chains in their structure (BCAAs) that are also considered “essential” because you must get them from your diet. These include leucine, isoleucine, and valine and they’re important largely because they make up 35% of the amino acids in muscle protein but also because research shows benefit in several applications.

Of supplements studied for applications in exercise, BCAAs show some of the most promise. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. There are 3 that have branched chains in their structure (BCAAs) that are also considered “essential” because you must get them from your diet. These include leucine, isoleucine, and valine and they’re important largely because they make up 35% of the amino acids in muscle protein but also because research shows benefit in several applications.

Muscle Protection & Repair

The fundamental idea behind weight-lifting is that through exercise you create tiny tears in muscle fibers that your body then repairs. In the repair process the muscle gets bigger and stronger. Minimizing muscle damage and injury, maximizing muscle synthesis, and replacing BCAAs (which are broken down with exercise) are our goals. BCAA supplementation has been shown to reduce training-induced muscle damage while creating a net anabolic (muscle-building) state, increasing muscle-protein synthesis. [1] [2] [3] [4] This therefore could have a 2-fold benefit: helping athletes perform better on subsequent exercise by reducing the risk of injury, and possibly promoting muscle growth.

Immune System Support

One of the concerns for serious athletes, particularly endurance athletes, is the effect on the immune system after intense or prolonged exercise. During this time immune function is lower resulting in increased risk of infection. BCAAs have been shown to modulate the immune system and inflammatory response in a favorable way. For those that want to know the details: BCAAs reverse a reduction in l-glutamine that is associated with symptoms of infection and lymphocyte (an immune cell) activity. (5) BCAAs also appear to recover mononuclear cell proliferation (a type of immune cell), modify cytokine production (inflammatory proteins), and shifts the immune response away from lymphokine activation to a Th1 type of response. [3] [6]

Other BCAA Benefits

BCAAs have also been shown to ameliorate muscle soreness when taken before and after exercise, [6] and may be particularly beneficial not only in weight-lifting, but in sports with varying intensity and those which require quick responses to different stimuli such as soccer and tennis. [7]

BCAA Dose

The optimal BCAA dose varies by person and there is not a straightforward answer. It likely varies between 5 and 12 grams before and after and part of this should probably come from post-workout protein. Studies have shown that a single bolus dose of 5 g per day of BCAAs has some benefit in terms of muscle recovery and immune support, but a greater benefit was seen at higher doses like 20g before and after, (9) a dose not easily achieved. Smaller doses also show benefit such as 14g, (10) and even 10g pre- and post-workout. (11) There seems to be not only a dose-dependent variation in effect, but also a greater effect in lower calorie diets. (10)

Can I just use BCAAs?

Even though amino acids are the building blocks of proteins you shouldn’t rely just on BCAAs for muscle recovery because whole protein is essential for optimal muscle recovery with amino acids beyond just the branched-chains. BCAAs alone do not have a lot of support for increasing muscle protein synthesis, but that’s where protein comes in.

Protein

The benefits of protein ingestion for muscle recovery are well-established. Higher protein diets have also been shown to help spare muscle loss in low calorie diets, (13) helping not only increase muscle protein synthesis but reduce muscle breakdown. (14) Higher protein diets have also shown to have the same benefits in reducing age-related muscle mass decline (also known as sarcopenia). (15) Furthermore, unlike carbohydrates and fat, there aren’t reserves of protein ready for your body to use.

Can I replace BCAAs with protein?

BCAAs help make up protein and as long as you are reaching your total protein goal for the day, you may not need extra BCAAs. However, they can provide additional benefit if you have trouble getting enough total protein, and for people who like to exercise in the fasted state BCAAs can be a great addition to a training program to give your muscles fuel before and after your workout. You can read more about this in the “Timing” section below.

How much protein?

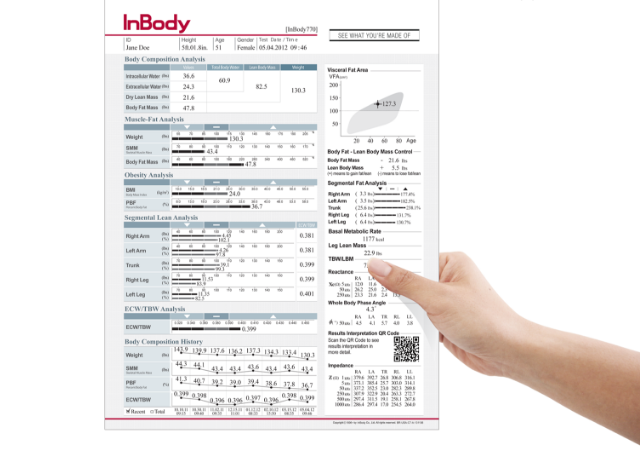

The right amount of protein will vary by person due to variations in genetics, age, intensity and type of exercise performed, health conditions, basal metabolic rate, fitness goals, and even the bacteria in your gut can influence how your body digests and responds to foods. In our office we use an InBody body composition analysis device to help us more precisely determine muscle mass and basal metabolic rate (calories burned in a day without additional exercise) which help us determine protein needs on an individual basis.

Studies have also shown that “exercise potentiates the response of muscle to protein ingestion up to 24 hours following the exercise bout” which emphasizes the importance of consuming sufficient total protein on exercise days. [16] In fact, some evidence suggests that reaching total protein goals for the day is more important than quality of protein or timing in long-term exercise interventions. [17]

You can find quite a few opinions out there on how much protein you need, largely because of all the variables involved! What is right for you is not right for everyone. Here are the recommendations from Netter’s Sports Medicine for daily protein consumption which can give you the ballpark to aim for: 1.6-1.7 g/kg for strength-training, 1.2-1.4 g/kg for endurance athletes, and possibly no benefit beyond 2.0 g/kg*. Approximations of these for several weights are found below to give you an idea of what that looks like:

| Body Weight | Strength-Training | Endurance |

| 120 lbs | 90 g protein | 70 g protein |

| 160 lbs | 120 g protein | 95 g protein |

| 200 lbs | 150 g protein | 115 g protein |

| 250 lbs | 185 g protein | 145 g protein |

These numbers should be taken with a grain of salt. As I said, there are many factors that influence how your body uses nutrients that (sorry to the perfectionists out there) even if you target these numbers perfectly it may not be right for you. Luckily, “overfeeding” energy (calories) with moderate to high protein results in gains in lean mass, not fat mass. This is not true for low protein diets. [18]

*A few reasons why you may need to consume higher amounts of protein than indicated above:

- You’re eating fewer meals in a day (<3)

- You are doing an intermittent fasting eating pattern

- There is an energy restriction (lower total calories, very low carb, or fasting for example)

- You are >65 years of age

Consuming 1.6g/kg/d – 2.7g/kg/d when there is energy restriction can help preserve fat free mass. [19] The proposed mechanism here is that even though insulin may be lower and your body is relying more on gluconeogenesis (creating energy from stores in a catabolic/breakdown state) it won’t need to rely on breaking down skeletal muscle for amino acids as much if plenty of protein is being ingested and amino acids are readily available.

Older Adults and Protein

Higher protein needs may also apply for older adults (greater than 65 years of age) who tend to have a lower muscle protein synthesis response to protein ingestion: [20]

- On non-exercise days, older adults should target 1.0-1.2g/kg/d

- Older adults with acute or chronic disease may have even higher protein requirements of 1.2-1.5 g/kg/d, and even more on exercise days. [21]

Protein targets should be individualized to physical function. A further benefit of higher protein consumption in older people is that low protein intake is associated with increased mortality, an association that may be related to increased dietary cysteine need for supporting glutathione synthesis (an important antioxidant). [22] (See more on this topic in the “Post” section of “Protein Timing”)

These protein recommendations are not right for everyone, especially if you have kidney disease in which case lower protein limits are often necessary, so please see a trained specialist to determine what is right for you.

Protein Sources

photo credit: National Cancer Institute

Food sources of protein can be just as effective as supplementation, however many people find it challenging to get enough protein in the right window of time when relying on food sources and the quality of the protein matters. [16]

Weighing in on Whey and Pea Protein

Whey and pea protein are both effective protein sources. Whey protein has been shown to stimulate muscle protein synthesis greater than other sources like casein and soy. [15] However, some people prefer pea protein for a few reasons, one of which is that it has the added benefit of being a plant protein. High plant protein intake has an inverse association with mortality. [23] Pea protein also tends to be more tolerated due to dairy allergy and more socially acceptable to some people because it is plant-derived. Whey has the most evidence for maximum muscle protein synthesis but, in my opinion, pea protein appears to be an excellent option with other benefits as well.

Food Sources

Reaching your total protein goal for the day is important and you don’t want to rely only on protein shakes. Meats aren’t your only source of protein of course either; you just have to become aware of other protein sources to increase your plant-based proteins, particularly if you’re going the vegetarian or vegan route. Just to give you ballpark ideas of protein amounts in different foods:

| Food | Serving Size | Protein |

| Boiled egg | 1 large | 6 g |

| Wild salmon | 3 oz | 21 g |

| Chicken breast | 3 oz | 24 g |

| Hemp hearts | 3 tsp | 10 g |

| Black beans | ½ cup | 19.5 g |

| Chia seeds | 2 tbsp | 6 g |

| Flaxseeds | 2 tbsp | 4 g |

| Quinoa | 1 cup, cooked | 8 g |

| Lentils | ½ cup | 9 g |

| Broccoli | 1 cup, chopped | 2.6 g |

| Asparagus | 6 medium spears | 2.6 g |

| Almonds | 10 nuts | 3 g |

| Walnuts | 10 halves | 3 g |

| Nutritional Yeast | 2 tbsp | 4 g |

Timing

Timing is a very important factor here because it changes what your body decides to do with the calories consumed such as repairing muscles vs. storing the energy. In one study, consuming protein closer to a workout (right before and right after) lead to 2x the gain in lean body mass and significant reduction in body fat percentage compared to consuming the protein 8 hours before and 8 hours after working out. [24]

This gives us evidence that optimizing muscle protein synthesis goes beyond reaching total protein goals in a day, that even at this basic level, timing matters. Eating protein near your workout allows your body to use those amino acids to fuel your muscles, rather than use them for another purpose.

More specifically, 20 grams of protein consumed every 3 hours was superior to 2 other protein intake regimens: 10 grams every 1.5 hours (8x) and 40 g every 6 hours (2x) in terms of muscle protein synthesis. [25]

Pre

Much of the discussion around nutrient timing focuses on how soon after a workout to get protein, but for optimal muscle protein synthesis it is important to get some amino acids prior to working out as well. In one study, with consumption of amino acids immediately prior to exercise there was 2.5x more amino acid uptake in muscles and greater muscle protein synthesis compared to consumption immediately after. [26] For this reason, if you prefer to work out fasted (i.e. before breakfast or if you do intermittent fasting) I would strongly consider using supplemental BCAAs for better results, giving your body something to work with while staying pretty low in calories (about 4 calories per gram).

The same was not true for protein. A small 2007 study by the same author showed that protein ingestion immediately before vs. immediately after does not have a significant difference in muscle amino acid uptake,[27] but if you’re using amino acids or working out fasted, it matters that you get them before.

Post

The generally accepted window in which you are ideally getting protein is within 30 minutes after your workout. (Most studies compare longer time periods to “immediately after”). This influences absorption of protein consumed and what your body uses it for. A 2001 study in the Journal of Physiology showed that 2 hours post-workout was too long to wait. In fact, there was no significant change in muscle fiber size in the group that waited 2 hours to supplement. [28]

A small study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition showed that 20 grams of protein during a 20-30 minute post-workout time frame was sufficient to maximally stimulate muscle protein synthesis. [29]

However, for older adults to reach maximum muscle protein synthesis, it appears that closer to 40 grams following resistance exercise is necessary. [30] This is because as we age, skeletal muscle becomes less sensitive to the anabolic effects of resistance exercise + protein. [31]

Protein + Other Additions

Protein shakes can vary in that some have a little bit of carbohydrate, extra BCAAs, or other additions like cocoa polyphenols that have been shown to enhance blood flow, [32] additional nutrients and vitamins, while others are essentially only protein. Consuming carbohydrate with protein after exercise does not enhance muscle protein synthesis beyond protein alone, [16] but still may be a good option for people if it is a breakfast or snack option. Other additions that could have some added benefit, if not to a small degree, may include l-arginine, l-glutamine, or creatine, for example… a discussion for another day.

Your Diet Needs to Match Your Routine

In order to get the most out of your exercise, as mentioned earlier, you need to have the right diet. This is a bigger topic than I’m going to dive into fully at this point but I frequently see women who are getting into weight lifting without eating enough. Carbohydrates seem to be the outcast of the macronutrients right now, even though they are the preferred energy source for muscles and the predominant fuel at the intensity at which most athletes are working. With the increase in popularity of paleo diets and higher fat diets (which have great attributes!) there seems to be a growing fear of carbohydrates. Carbs can be healthy, especially when you’re getting them from complex carbohydrates and fruit.

One of the most important takeaways I hope you get from this is that your diet and supplementation regimen should be tailored to you and that foundations of health (sleep, nutrition, mental health, etc) are also foundations for a healthy body weight and optimizing body composition.

Works Cited

-

- Branched-chain amino acid supplementation before squat exercise and delayed-onset muscle soreness. Shimomura, Y, et al., et al. 3, 2010, Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab, Vol. 20, pp. 236-44.

- Amino acid supplements and recovery from high-intensity resistance training. Sharp, CP and Pearson, DR. 4, 2010, J Strength Cond Res, Vol. 24, pp. 1125-30.

- Branched-chain amino acid supplementation does not enhance athletic performance but affects muscle recovery and the immune system. Negro, M, et al., et al. 3, 2008, J Sports Med Phys Fitness, Vol. 48, pp. 347-51.

- Exercise promotes BCAA catabolism: effects of BCAA supplementation on skeletal muscle during exercise. Shimomura, Y, et al., et al. 6, 2004, J Nutr, Vol. 134, pp. 1583S-1587S.

- The effect of BCAA supplementation upon the immune response of triathletes. Bassit, RA, et al., et al. 7, s.l. : Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2000, Vol. 32.

- Branched-chain amino acid supplementation and the immune response of long-distance athletes. Bassit, RA, et al., et al. 5, 2002, Nutrition, Vol. 18, pp. 376-9.

- Branched-chain amino acid ingestion can ameliorate soreness from eccentric exercise. Jackman, SR, et al., et al. 5, 2010, Med Sci Sports Exerc, Vol. 42, pp. 962-70.

- The effect of branched chain amino acids on psychomotor performance during treadmill exercise of changing intensity simulating a soccer game. Wisnik, P, et al., et al. 6, 2011, Appl Physiol Nutr Metab, Vol. 36, pp. 856-62.

- Exercise-induced muscle damage is reduced in resistance-trained males by branched chain amino acids: a randomized double-blind, placebo contrlled study. Howatson, Glyn, et al., et al. 20, s.l. : J Int Soc Sports Nutr, 2012, Vol. 9.

- In a single-blind, matched group design: branched-chain amino acid supplementation and resistance training maintains lean body mass during caloric restricted diet. Dudgeon, Wesley D, Kelley, Elizabeth P and Scheett, Timothy P. 1, s.l. : J Int Soc Sports Nutr, 2016, Vol. 13.

- Branched-chain amino acid supplementation attenuates a decrease in power-producing ability following acute strength training. Gee, TI and Deniel, S. s.l. : J Sports Med Phys Fitness, 2016.

- Protein blend ingestion following resistance exercise promotes human muscle protein synthesis. Reidy, PT, et al., et al. 4, 2013, J Nutr, Vol. 143, pp. 410-6.

- Higher compared with lower dietary protein during an energy deficit combined with intense exercise promotes greater lean mass gain and fat mass loss: a randomized trial. Longland, TM, et al., et al. 3, 2016, Am J Clin Nutr, Vol. 103, pp. 738-46.

- The anabolic response to a meal containing different amounts of protein is not limited by the maximal stimulation of protein synthesis in healthy young adults. Kim, IY, et al., et al. 1, 2016, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, Vol. 310, pp. E73-80.

- Supplemental protein in support of muscle mass and health: advantage whey. Devries, MC and Phillips, SM. 1, 2015, J Food Sci, Vol. 80, pp. A8-A15.

- Dietary protein for muscle hypertrophy. Tipton, KD and Phillips, SM. 2013, Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser, Vol. 76, pp. 73-84.

- Role of ingested amino acids and protein in the promotion of resistance exercise-induced muscle protein anabolism. Reidy, PT and Rasmussen, BB. 2, 2016, J Nutr, Vol. 146, pp. 155-83.

- Role of protein and amino acids in promoting lean mass accretion with resistance exercise and attenuating lean mass loss during energy deficit in humans. Churchward-Venne, TA, et al., et al. 2, 2013, Amino Acids, Vol. 45, pp. 231-40.

- Considerations for protein intake in managing weight loss in athletes. Murphy, CH, Hector, AJ and Phillips, SM. 1, 2015, Eur J Sport Sci, Vol. 15, pp. 21-8.

- Aging is accompanied by a blunted muscle protein synthetic response to protein ingestion. Wall, BT, et al., et al. 11, 2015, PLoS One, Vol. 10, p. e0140903.

- Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE study group. Bauer, J, et al., et al. 8, 2013, J Am Med Dir Assoc, Vol. 14, pp. 542–59.

- An increased need for dietary cysteine in support of glutathione synthesis may underlie the increased risk for mortality associated with low protein intake in the elderly. McCarty, MF and DiNicolantonio, JJ. 5, 2015, Age (Dordr), Vol. 37, p. 96.

- Association of aminal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Song, Mingyang, et al., et al. 2016, JAMA Intern Med.

- Effects of supplement timing and resistance exercise on skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cribb, PJ and Hayes, A. 11, 2006, Med Sci Sports Exerc, Vol. 38, pp. 1918-25.

- Timing and distribution of protein ingestion during prolonged recovery from resistance exercise alters myofibrillar protein synthesis. Areta, JL, et al., et al. 9, 2013, J Physiol, Vol. 591, pp. 2319-31.

- Timing of amino acid-carbodhydrate ingestion alters anabolic response of muscle to resistance exercise. Tipton, KD, et al., et al. 2, 2001, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, Vol. 281, pp. E197-206.

- Stimulation of net muscle protein synthesis by whey protein ingestion before and after exercise. Tipton, KD, et al., et al. 1, 2007, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, Vol. 292, pp. E71-6.

- Timing of postexercise protein intake is important for muscle hypertrophy with resistance training in elderly humans. Esmarck, B, et al., et al. 1, 2001, J Physiol, Vol. 535, pp. 301-11.

- Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men. Moore, Daniel, et al., et al. 1, 2009, Amer J Clin Nutr, Vol. 89, pp. 161-168.

- What is the optimal amount of protein to support post-exercise skeletal muscle reconditioning in the older adult? Churchward-Venne, TA, et al., et al. Feb 19, 2016, Sports Med.

- Alterations in human muscle protein metabolism with aging: protein and exercise as countermeasures to offset sarcopenia. Churchward-Venne, TA, Breen, L and Phillips, SM. 2, 2014, Biofactors, Vol. 40, pp. 199-205.

- Cardioprotective effects of cocoa: clinical evidence from randomized clinical intervention trials in humans. Arranz, S, et al., et al. 6, 2013, Mol Nutr Food Res, Vol. 57, pp. 936-47.

33. Madden, Christopher and Putukian, Margot, Young, Craig, McCarty, Eric. Netter’s Sports Medicine. Philadelphia : Saunders, 2010.